Most bitcoin investors are just one mistake, one breach, or one bad setup away from watching their generational wealth vanish.

Our latest research helps you navigate how to store bitcoin safely, and evaluate security on exchanges vs self-custody.

In this report:

- An in-depth look into the bitcoin custody landscape

- How to determine if your exchange is secure

- How to decide if self-custody is right for you

Or continue reading…

Table of Contents

Introduction

Bitcoin is one of the most promising technologies of our time, offering individuals the ability to take control of their financial lives with money that is scarce, transparent, and incorruptible. Unfortunately, most bitcoin investors are just one mistake, one breach, or one bad setup away from watching their generational wealth vanish.

Over the past sixteen years, more than 3 million bitcoin have been either permanently lost through poor key management or lost by exchanges to hacks, insider theft, and bankruptcy. Bitcoin is maturing as an asset, but the ways many people and exchanges secure it remain dangerously immature.

Investors are too often trapped between two imperfect choices: exchanges that still fail basic security standards, and self-custody where the learning curve is steep and the margin for error is zero.

While there are many “how-to” guides on specific storage setups, this report helps you zoom out and consider custody as a whole. It covers how to evaluate an exchange, when and how to self-custody, and best-practices to follow, in addition to a comprehensive overview of Bitcoin’s custody landscape today.

Even if you already self-custody, understanding the broader custody landscape still matters. If you want friends and family to benefit from bitcoin but they’re not ready to take on the responsibility of self-custody, you’ll need to help them choose a safe home for their savings.

Furthermore, custody is not a binary decision. Many experienced holders use a blend of self-custody, exchanges, and other solutions. The right approach depends on an individual’s skill level, risk tolerance, and personal circumstances.

A subset of bitcoin holders strongly believe that every person should self-custody their bitcoin. While we encourage everyone to consider self-custody, we disagree with this perspective. Given how many people today struggle to remember passwords and follow basic security best practices, much of the world is not ready for this level of responsibility. We will further elaborate on this perspective in this report.

How Bitcoin Revolutionizes Ownership

Sixteen years ago, bitcoin was introduced as the world’s only incorruptible digital money. Today, bitcoin is best known as a store-of-value and is rapidly emerging as a global reserve asset.

Less appreciated is how Bitcoin revolutionizes the way people can store wealth. It is the first digital financial asset that can be owned directly, which has profound implications for our financial system.

Historically, only tangible commodities like gold or wheat could be owned directly. Other physical assets, such as real estate, represent claims tied to an issuer or intermediary. The same is true for financial assets like stocks and bonds: you don’t hold the asset itself, only a claim to it. Bitcoin breaks this pattern through the use of private keys, enabling true, direct ownership of digital money.

Bitcoin is stored fundamentally differently than traditional financial assets, and has required the creation of an entirely new custody framework that has developed over the past 16 years.

This new framework has enabled meaningful advances in custody design. Individuals and businesses can now self-custody their savings. Financial institutions are now incentivized to demonstrate radical transparency through Proof of Reserves attestations. Bitcoin’s multisignature technology enables ownership to be distributed across multiple parties and locations.

To understand bitcoin custody today, it helps to look at the foundational building blocks on which it is built. This rest of this chapter highlights the key developments in Bitcoin’s short history that have shaped the current custody landscape.

Public-private key cryptography: The backbone of bitcoin custody

Bitcoin is secured through public-private key cryptography. Every bitcoin wallet is associated with a unique private key: a long string of numbers and letters that functions like a digital password. Whoever controls this private key can spend the bitcoin it secures.

From the private key, a corresponding public key is generated by the wallet, and from that, a Bitcoin address is derived. The address can be safely shared as it is the destination to receive funds. The private key, however, must remain secret. If it is lost, the bitcoin tied to it become permanently inaccessible. If it is stolen, the thief can take all of the bitcoin and there would be no way for you to undo the damage as transactions are irreversible.

To spend bitcoin, the private key is used to create a digital signature: a cryptographic proof that authorizes a transaction. A signature mathematically demonstrates that the spender controls the private key without ever revealing the key itself.

Bitcoin custody is the practice of safeguarding private keys, whether through individual control (self-custody) or by relying on third-party custodians that secure them on behalf of users.

Below we will cover developments in bitcoin custody that have been built upon public-private key cryptography.

The origins of bitcoin custody

Satoshi’s original release of Bitcoin in January 2009 bundled together all aspects of the software: The full node, wallet, and mining all existed within the same interface. If you wanted to store, send, or receive bitcoin, you had to run this full node software. In other words, custody was inseparable from full blockchain validation.

Paper and software wallets

Wallet functionality split from the original all-in-one Bitcoin client in 2011. This made custody possible without running a full node, lowering the technical barrier for everyday users.

The first widely adopted software wallet, Electrum, was released on November 5, 2011, enabling key management on ordinary laptops. Software wallets also laid the groundwork for features such as watch-only wallets and multi-device setups, which later became essential in both individual and institutional custody.

At the same time, paper wallets emerged. Users could generate private keys on their own, print or write them down alongside a corresponding Bitcoin address and QR code, and store the paper offline. Paper wallets offered individuals a simple way to keep their bitcoin in cold storage, safe from online threats.

Multisignature support

Before multisignature support existed, every bitcoin transaction depended on a single private key. If that key was lost, stolen, or compromised, the funds were irretrievably gone.

Multisignature (multisig) transactions solved this by allowing bitcoin to be controlled by multiple keys instead of just one. A wallet could require, for example, 2 out of 3 keys to authorize a transaction, making theft or accidental loss far less likely.

This capability became formalized in early 2012 through Bitcoin Improvement Proposals (BIP) 11 and 16, which added native multisig support to the protocol. For custody, this was a breakthrough. Multisig allowed keys to be distributed across different people, devices, and geographic locations, removing single points of failure.

Multisig has become the backbone of enterprise-grade custody. Exchanges and custodians use it to require multiple approvals for transactions, build in recovery keys for emergencies, and create stronger security policies. Recently, multisig has become highly accessible for individuals who self-custody, as several providers have simplified the experience to set up and maintain a multisig.

Seed phrases and deterministic wallets

Before modern wallet standards, backing up bitcoin was cumbersome and error-prone. Each new address produced a new private key, meaning users had to store many independent backups. Losing just one key meant losing the funds tied to it, and coordinating secure setups across devices was difficult.

Deterministic wallets solved this by allowing an entire wallet to be generated from a single root. Instead of managing dozens or hundreds of keys, users could back up one piece of information and restore everything from it.

Two important proposals formalized this approach:

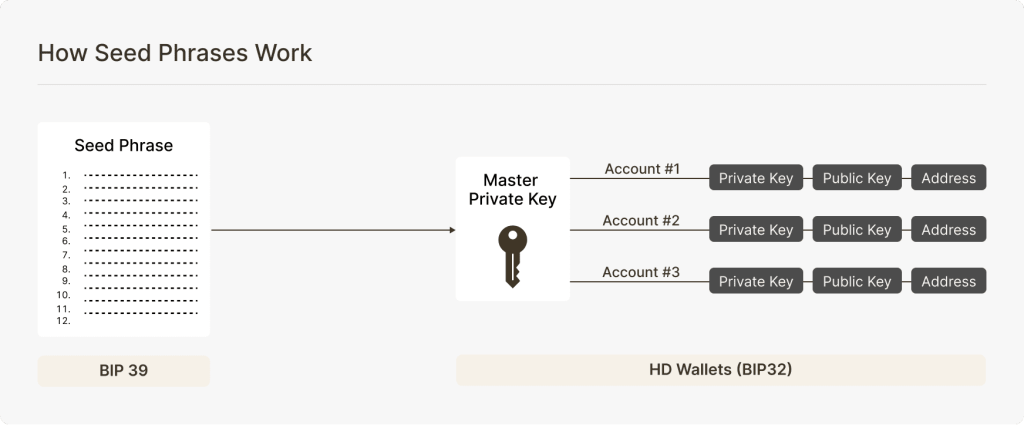

Hierarchical deterministic wallets (BIP32, 2012) introduced the idea of deriving a full tree of addresses from a single master seed. This also made it possible to share an extended public key (xpub) for viewing transactions without exposing spending access, and enabled more advanced, multi-device signing setups.

Mnemonic seed phrases (BIP39, 2013) made backups far more user-friendly by encoding the master seed as a list of 12 or 24 words. This human-readable format preserves full cryptographic strength and allows users to recover their entire wallet even if the original device is lost or destroyed.

Together, these innovations made custody far more practical. They allowed individuals to recover from device loss and set up standardized cold storage procedures. For institutions, they also introduced reliable ways to restore and organize accounts, and sharing of viewing keys for auditors or compliance teams.

Hardware wallets

By 2013, experimentation began with dedicated devices designed solely for storing bitcoin keys and signing transactions. Until then, most users relied on hot wallets: software wallets that keep private keys on internet-connected devices, making them convenient but more exposed to malware and phishing risks. Hardware wallets solve this by generating and protecting keys in a secure, offline environment and signing transactions internally.

The first widely adopted commercial product was the Trezor Model One, launched in 2014. It allowed users to confirm transaction details on a small screen and required button presses to approve spending, making it much harder for malware on a connected PC to steal funds. Soon after, Ledger introduced a hardware wallet which used a secure element chip (the same type of tamper-resistant component found in credit cards) and an operating system to further isolate sensitive data and applications.

Hardware wallets were a breakthrough in bitcoin custody, overtime becoming the default choice for self-custody among individuals. They also started being used in institutional custody workflows as building blocks for larger cold storage or multi-party signing systems.

Proof of Reserves

In March 2014, after the world’s largest exchange collapsed, Kraken introduced the first cryptographic Proof-of-Reserves (PoR) audit. The method was inspired by a proposal from Bitcoin developer Greg Maxwell.

Proof of Reserves allows customers to check that their balances are included in an exchange’s reserves without exposing their personal information. It enables exchanges to demonstrate solvency without moving funds or disclosing sensitive customer data.

PoR is not a replacement for a traditional financial audit, since it does not account for fiat liabilities, corporate debt, or off-chain obligations. However, it still would have prevented the majority of large exchanges collapses by exposing insolvencies at an earlier stage.

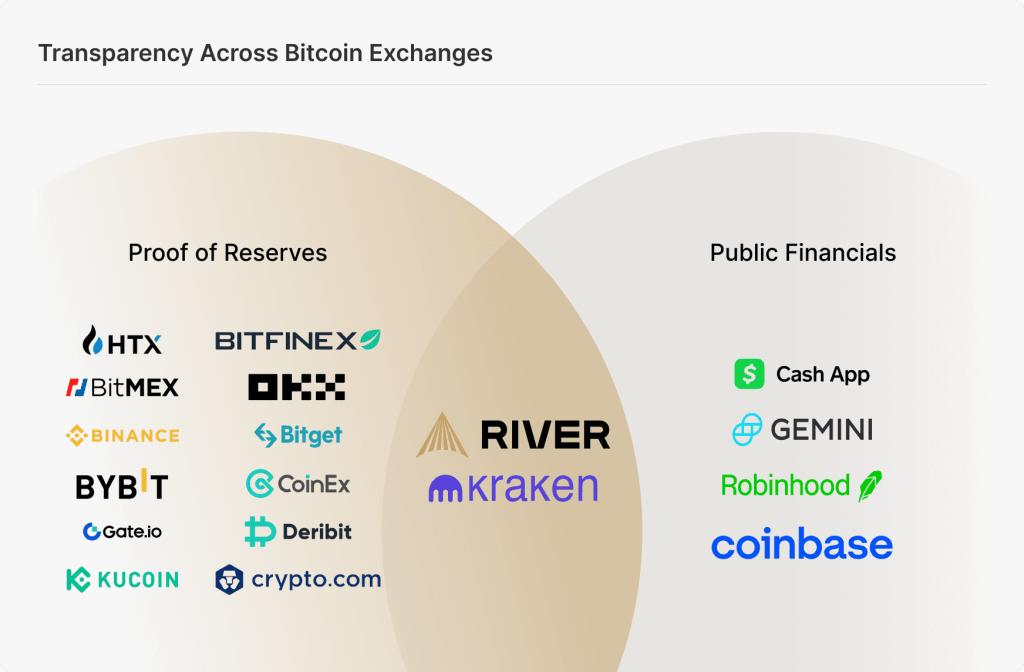

Although Proof-of-Reserves has gained traction across the industry, it is far from universally implemented. Major exchanges, including Coinbase, have yet to release a PoR audit and continue to expect clients to simply trust their reserve practices.

Bitcoin custody today uses many of the developments outlined above. The next chapter will build on this to provide a comprehensive breakdown of bitcoin custody in 2025.

Bitcoin Custody in 2025

Today, over $1 trillion in bitcoin is secured through a wide range of custody setups. Understanding the different forms of bitcoin storage is essential for anyone looking to evaluate risk, security, or the degree of control they have over their assets. This section helps readers make sense of the landscape by outlining major categories of bitcoin custody and comparing them using publicly-available data.

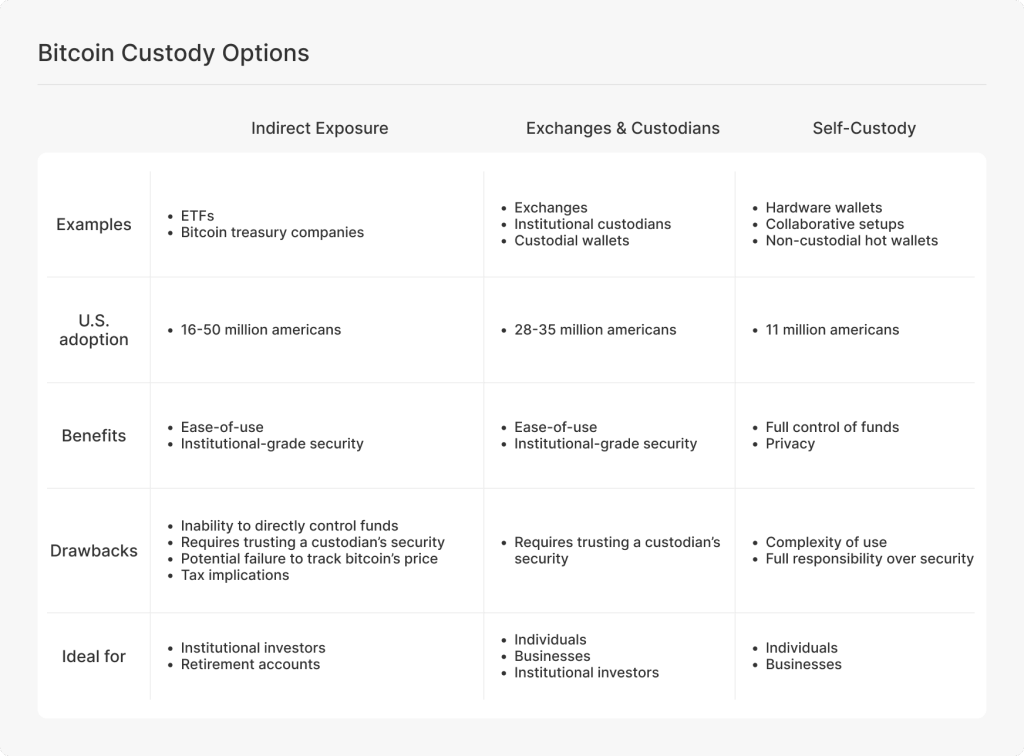

At a high level, bitcoin custody can be categorized into three groups, as shown in the visual below.

Indirect exposure refers to owning a financial contract that tracks bitcoin’s price rather than holding actual bitcoin on the network. Investors in these products do not possess or control bitcoin directly. Instead, they gain price exposure through instruments such as:

- Exchange-traded funds (ETFs): Traded through traditional brokerage accounts.

- Wrapped bitcoin: Tokens pegged to the value of bitcoin.

- Bitcoin treasury companies: Publicly traded firms whose core business is providing shareholders with bitcoin price exposure.

Indirect exposure products appeal to investors who, for regulatory reasons or otherwise, are unable or unwilling to own real bitcoin. These products are typically ideal for institutional investors, such as registered investment advisors, who may be prohibited from investing in bitcoin directly.

The downsides of these products are clear: indirect exposure does not provide true ownership or the ability to transact with bitcoin. Converting to actual bitcoin requires selling the product (a taxable event) and rebuying elsewhere. Some instruments, such as stocks of bitcoin treasury companies, may also diverge from bitcoin’s price over time.

Even so, indirect exposure remains the most accessible bridge to bitcoin within the legacy financial system. According to the Nakamoto Project and publicly available ETF data, as many as 50 million Americans have some amount of indirect exposure to bitcoin, whether through retirement plans, managed portfolios, or personal investments. These products are widely accessible and a major driver of bitcoin adoption, even though they do not provide the benefits of holding bitcoin directly.

Exchanges & custodians refer to separate entities that hold and manage the private keys on behalf of the user, and are ideal for investors who are not comfortable with keeping some or all of their bitcoin holdings in self-custody.

A core principle of holding bitcoin on an exchange is that users must always retain the ability to withdraw their bitcoin into self-custody. Without this option, the user does not truly own bitcoin but instead holds only a contractual claim or indirect exposure to its price. Roughly 30 million Americans own bitcoin held by an exchange or custodian according to the Nakamoto Project.

Self-custody refers to direct ownership of bitcoin through the control of private keys, and is ideal for investors who are confident in their ability to take full responsibility for managing their bitcoin. Common examples of self-custody include:

- Hardware wallets and offline setups: Devices or other methods such as paper wallets that keep keys offline.

- Non-custodial hot wallets: App-based wallets in which only the user controls access to the private keys.

- Collaborative custody: Multi-signature setups in which the user maintains a controlling share of the keys.

While self-custody introduces additional complexity, it is the only method that grants true ownership of bitcoin. It also uniquely minimizes counterparty risk, as control over the assets remains entirely in the hands of the holder. However, with this autonomy comes significant responsibility; if you lose your private keys, your bitcoin is permanently lost.

While indirect exposure and exchanges are the most prominent ways to access bitcoin, the majority of bitcoin circulating today is held in self-custody.

The dominance of self-custody among bitcoin holdings is the result of a few factors.

First, history has shown that exchanges and third-party custodians are vulnerable to hacks, scams, and theft, incidents that continue to this day. For much of Bitcoin’s history, indirect exposure options such as ETFs did not exist, leaving investors with few trusted alternatives. Even today, many custodians fail to follow best practices for safeguarding client assets and lack transparency into their operations. In this environment, self-custody remains a preferred choice for bitcoin holders with sufficient knowledge.

Second, self-custody is often the natural progression for investors as their holdings and understanding of Bitcoin grow. A new buyer with $100 worth of bitcoin may not be concerned about optimizing for security, but a long-term accumulator with meaningful exposure will inevitably take custody more seriously. Finally, more than half of all bitcoin were mined before exchanges had meaningful adoption. For holders who never sold these early coins, there has been little reason to move them out of self-custody.

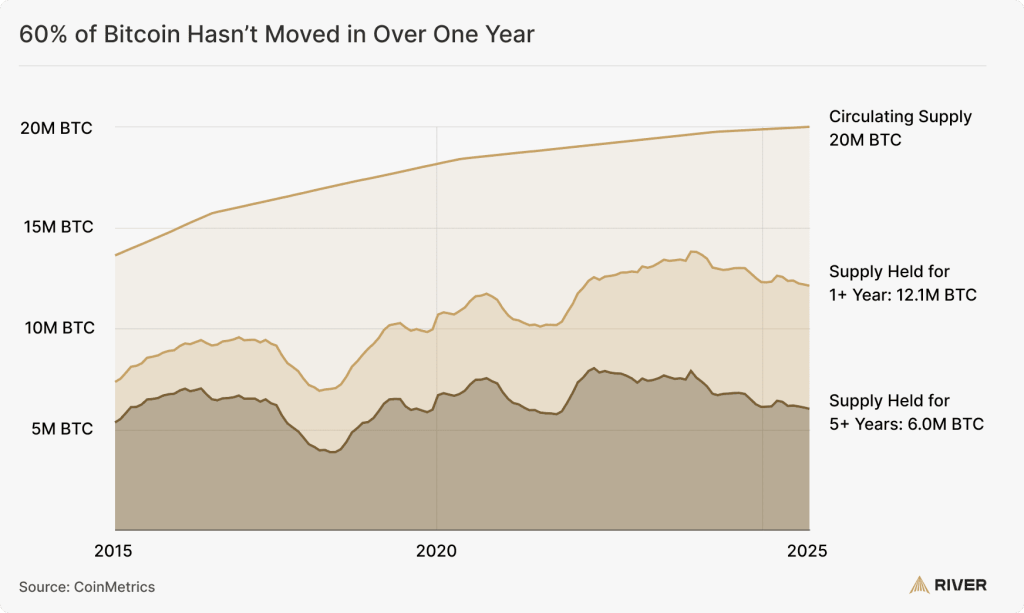

This trend is reflected in the data: the majority of bitcoin are held by long-term investors. More than 12 million bitcoin have not moved in the past year, and over 6 million have remained untouched for half a decade. Many of these holdings are likely stored in secure, offline environments.

Holding Bitcoin on an Exchange

More than 100 million people worldwide hold their bitcoin on exchanges according to multiple industry estimates. However, not all exchanges offer the same level of protection, and some still come with elevated risk.

This section helps you decide if holding bitcoin on an exchange is an appropriate option for you. We answer a few important questions:

- What are the benefits and drawbacks of using an exchange?

- Who should hold their bitcoin on an exchange?

- How should you select an exchange for long-term holdings?

- What custodial options exist beyond exchanges?

What are the benefits and drawbacks of using an exchange?

In 2025, many exchanges provide a level of security and professionalism that is difficult to replicate on your own. Their systems are designed with multiple layers of redundancy to eliminate single points of failure and reduce the risk of insider theft, hacks, or operational mistakes.

Some exchanges are becoming more transparent, either by voluntarily publishing their financials or by doing so as part of public-company reporting requirements. Nearly half of all bitcoin held on exchanges can be independently verified as fully reserved through proof of reserves attestations.

A reputable exchange may provide a higher level protection of your bitcoin compared with self-custody, depending on what options are available and your technical ability to handle your own setup. Still, it’s important to understand the risks that come with using an exchange and how they can be addressed. Below we will look at potential downside scenarios and how to prevent them.

Risks of holding bitcoin on an exchange

- Losing your bitcoin: This can occur either through failures of the exchange itself, or by your personal account being compromised.

- Personal information being compromised: Under the Bank Secrecy Act, exchanges are required to gather sensitive personal information such as your name, date of birth, and address. If compromised, malicious actors can use this information to conduct physical or digital attacks to steal your bitcoin.

How much bitcoin has been lost by exchanges?

It is impossible to determine the full extent of bitcoin lost by exchanges or the amount of personal information that has been compromised. However, large-scale losses leading to lawsuits or bankruptcies are typically documented in the public record, which enables us to develop low-end estimates of exchange losses. In some instances, losses were repaid to depositors in part or in full, usually years later, which is not accounted for in the data below.

Before 2020, exchange hacks were the most common form of loss, largely due to immature security setups such as having private keys stored online with a single signature. When viewed in bitcoin terms, exchange losses appear to be decelerating, with the vast majority having occurred before 2013.

However, the true economic impact on users is better captured by the dollar value of bitcoin at the time of each loss. From this perspective, exchange losses remain a significant source of risk.

In 2022 alone, more than 100,000 BTC worth over $2 billion were lost by exchanges that offered yield on bitcoin holdings, many of which became insolvent after suffering losses on bitcoin loans. Additionally, cases of embezzlement, in which exchange employees steal customer funds, account for approximately $2.6 billion in losses since 2020.

When to hold your bitcoin on an exchange

Nearly every bitcoin investor uses an exchange in some capacity. Even those who primarily self-custody still rely on exchanges to buy and withdraw bitcoin, and many intentionally keep a portion of their holdings on an exchange for custody diversification or convenience. In all cases, it’s important to prioritize security when choosing an exchange, and use available tools to protect both your assets and your personal information.

For anyone holding more bitcoin than they can afford to lose, security should be the primary factor in deciding where the majority of funds are stored. If you believe a reputable exchange can provide stronger protection than you can on your own, holding your bitcoin on an exchange is often the safer choice.

How to select an exchange to hold bitcoin long-term

A secure exchange should stand out with three qualities:

- A highly secure infrastructure: As demonstrated by a track record of safeguarding client assets from loss and theft.

- Transparency and auditability: The ability for clients to independently confirm their assets are secure.

- Tools to protect your account: Strong security features that protect individual accounts from losses related to attacks, estate-related events, and bankruptcy.

Highly-secure infrastructure

The top priority of any bitcoin exchange should be keeping your bitcoin and personal information safe. Exchange security infrastructures are typically highly complex. While the technical details can be difficult to navigate, there are a few important qualities that can help you evaluate if an exchange is truly secure and reputable.

No history of losses: The first and most important factor to know about an exchange is its track record. Before using any exchange, review whether its clients have ever lost access to their deposits, why those incidents occurred, and how the exchange handled them.

No history of data breaches: Track record also applies to an exchange’s ability to protect user data. Six major U.S. exchanges have suffered data breaches exposing millions of people to attempted phishing attacks, scams, and other attacks, resulting in at least dozens of publicly recorded cases of actual theft. If you are considering an exchange with a history of data breaches, investigate the causes and steps taken to prevent future incidents.

Geographically redundant cold storage: Today, the vast majority of exchanges use multiple layers of redundancy to remove single points of failure. Ensuring private keys are distributed geographically is crucial, either through multi-sig or multi-party computation.

Core custody non-reliant on third parties: A quick and convenient way to launch an exchange is to outsource custody and other core infrastructure components to a third party. This decision comes with a tradeoff: Outsourcing limits the ability for the exchange to fully understand and control the security of its infrastructure.

Reputable exchanges prioritize building and maintaining their infrastructure in-house to minimize external dependencies, so that no third parties ever have access to private keys. While this approach may result in a slightly longer development timeline, it provides a higher level of security assurance to clients.

Client deposits held in full reserve: A trustworthy exchange should never lend, rehypothecate, or otherwise use your deposits for activities that aren’t in your best interest without your consent. Doing so introduces counterparty risk that could lead to insolvency or loss of funds. Full-reserve custody ensures that bitcoin is always available to clients, but this can only be verified with the right transparency measures.

Transparency and auditability

“Don’t trust, verify” is a common phrase among bitcoiners, and it’s especially relevant when evaluating exchanges. The more an exchange can demonstrate that your assets are safe, fully reserved, and that the business itself is financially sound, the less trust you need to place in them.

Proof of Reserves: Proof of Reserves audits allow exchanges to cryptographically verify that client deposits are fully backed by on-chain assets. By publishing verifiable attestations without revealing sensitive account data, custodians provide clients with independent assurance that funds are held in full and not rehypothecated.

Public financials: Regularly publishing audited financial statements gives clients assurance into the long-term viability of their exchange. Traditional banking offers a useful precedent: chartered banks are required by law to publicly disclose their financial statements, enforcing transparency and instilling confidence in the financial system.

SOC II certification: While there are many certifications a bitcoin exchange can pursue, SOC II (Service Organization Control Type II) is the most important for demonstrating strong security. It requires an independent audit of an exchange’s security, availability, and data integrity controls. By achieving and maintaining this certification, exchanges demonstrate that their internal systems meet rigorous standards for operational transparency and client data protection.

Tools to protect your account

It’s important to remember that even if you trust an exchange to secure your assets, you are still responsible for protecting your account from scams and other attacks.

Non-SMS two-factor authentication: All top exchanges offer two-factor authentication using app-based or hardware-based methods. Using these instead of SMS (text messages) significantly reduces the risk of SIM-swapping and phishing attacks. This ensures that even if login credentials are compromised, unauthorized access to client accounts remains extremely difficult.

Inheritance features: Traditionally, transferring funds after a depositor’s passing depends on legal intermediaries; this process is often slowed by probate proceedings, contested wills, and jurisdictional hurdles. Dedicated bitcoin inheritance features, offered by only 2 of the 10 largest U.S. exchanges, enable asset transfer through cryptographic verification and predetermined conditions. This approach reduces the risk of lost access, legal disputes, and administrative delays while preserving the owner’s full control and privacy throughout their lifetime.

Custom spend limits: Restricting how much bitcoin can be withdrawn from your account is one of the best ways to prevent attacks such as malware, phishing, scams, and phone theft. Even if account access is compromised, attackers cannot steal more than a predefined amount, such as $500 within a week.

Address whitelisting: Address whitelisting restricts all withdrawals to a fixed set of pre-approved addresses. This can be used in addition to, or as an alternative to, spend limits with more flexibility, since you can allow unlimited withdrawals to trusted, pre-approved addresses.

Assets can be held in a trust company: Holding bitcoin through a regulated trust company adds a layer of legal and financial protection. Trust companies are fiduciaries, legally obligated to act in clients’ best interests, and operate under direct oversight from state or federal banking regulators. Client assets are segregated from the company’s own balance sheet, meaning they are not subject to creditors if the custodian fails or declares bankruptcy. This structure also simplifies estate and inheritance processes, since holdings are managed under established trust laws rather than through standard exchange terms of service.

Custodial options beyond exchanges

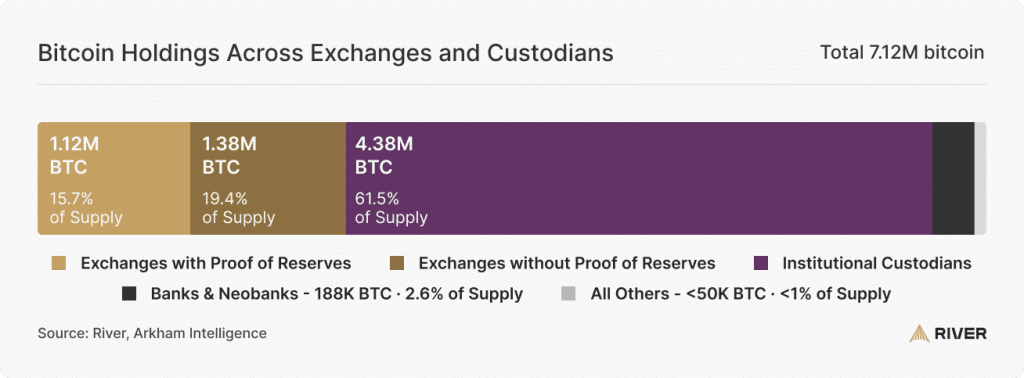

While exchanges are the primary gateway for most individual investors, they now hold only 35% of custodial bitcoin, compared to over half in 2021. Below we briefly explain existing custodial options beyond exchanges.

Institutional custodians serve the specialized needs of heavily regulated entities such as asset managers, ETFs, and other financial institutions that require robust governance and compliance capabilities. These providers are typically qualified custodians, meaning they are legally authorized to hold assets on behalf of regulated institutional clients. With the recent rise of bitcoin adoption by institutions, these custodians now account for the majority of bitcoin held with third parties.

Neobanks, such as Robinhood, and chartered banks, particularly abroad, are rising in popularity for their appeal to investors who prefer to manage all of their finances on one platform. While convenient, custody through banks and neobanks often involves limited withdrawal functionality and less transparency around how bitcoin is stored compared to bitcoin-focused exchanges and custodians. Many such companies also outsource their custody infrastructure to third-parties, introducing an additional layer of risk.

Custodial wallets are app-based services that manage private keys on behalf of the user. They are well-suited for individuals who frequently transact with bitcoin, but these wallets generally lack the advanced security features and transparency required for secure long-term storage.

Multi-institutional custody involves distributing control of private keys among multiple independent custodians located in different jurisdictions. By requiring several parties to jointly authorize transactions, this model mitigates the risk posed by any single custodian being compromised. As a relatively new custodial approach, its long-term adoption and prevalence in the industry remain to be seen.

Federated custody is a model in which a group of trusted individuals or entities collectively secures users’ bitcoin, typically using multisig. Unlike multi-institutional setups that use professional custodians, federated custody often involves smaller, community-based groups or federations.

Holding Bitcoin in Self-Custody

In the 2008 whitepaper, Bitcoin was introduced as “a purely peer-to-peer version of electronic cash” enabling digital money to be stored and sent without relying on any trusted intermediaries.

Seventeen years later, Bitcoin in 2025 continues to live up to this original vision. More than $800 billion worth of bitcoin is held in self-custody. Investors with sufficient knowledge can choose from dozens of secure, open-source tools to maintain full control over their holdings and transact as they please.

This chapter will help you understand how self-custody works and determine whether it’s right for your needs. We’ll answer the following questions:

- What are the benefits and drawbacks of self-custody?

- What options exist for self-custody?

- Who should hold their bitcoin in self-custody?

- What are the best practices for self-custody?

Benefits and drawbacks of self-custody

When done properly, self-custody gives you full sovereignty over your bitcoin by eliminating the need to trust intermediaries. In the right conditions, it can also offer greater security and privacy compared to exchanges and other third party solutions.

However, self-custody requires individuals to take full responsibility for their holdings, learn how to properly secure their bitcoin, and accept the consequences of any mistakes. This makes it essential to understand every potential risk and how to mitigate them.

Risks of Self-Custody

There are two primary risks associated with self-custody:

- Loss of keys: If you lose a controlling share of the private keys to your bitcoin, the funds become permanently inaccessible.

- Key theft: If a malicious actor gains access to a controlling share of your keys, your bitcoin can be stolen and is likely unrecoverable.

How much bitcoin has been lost through self-custody?

There are hundreds of documented cases of self-custody losses caused by key theft. However, for most users, the primary risk is self-imposed losses caused by losing access to keys or backups.

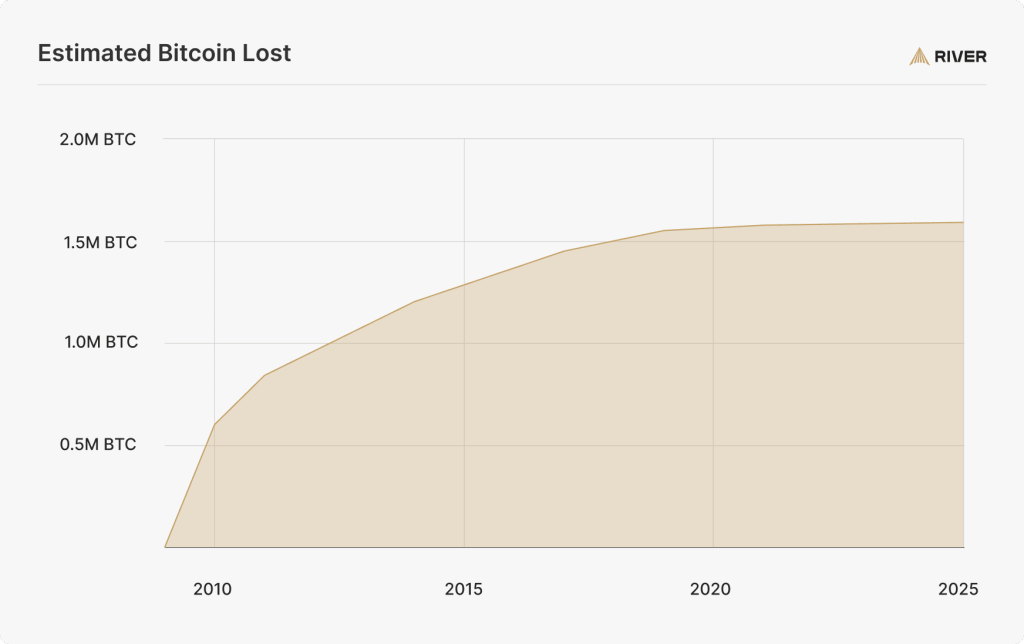

These permanent, self-imposed losses can be estimated using on-chain heuristics; specifically, by treating a subset of coins that have remained unmoved since a certain date as likely lost.

Using this approach, we conservatively estimate that 1.57 million bitcoin have been permanently lost, with 98% of those losses occurring before 2020. While it’s impossible to determine how much was lost due to self-custody specifically, it is reasonable to assume that the vast majority of these coins were held outside of custodial platforms.

When and how to practice self-custody

Choosing to self-custody your bitcoin is an important and nuanced decision. We will cover three key questions to guide you through this process:

- Is self-custody right for you?

- Which setup should you choose?

- How can you manage your setup securely?

Is self-custody right for you?

We recommend that at a minimum, every bitcoin investor learn the basics of using a wallet self-custodially. This helps you understand the underlying technology and make an informed decision about whether you want to self-custody more of your bitcoin. The most important part about self-custody is that you know how to do it, even if you don’t want to do it right now.

To get started with a small amount, we recommend our guide: How to get started with self-custody.

The decision tree below can help you decide if you should hold more of your bitcoin in self-custody.

When to self-custody your bitcoin

Another way of approaching the choice to self-custody is that if you need to be told to do it, you probably aren’t ready for it yet. Many newcomers to Bitcoin are rapidly pushed to self-custody by veterans, but many of them are far from ready and don’t understand what they are getting themselves into. This becomes evident when considering inheritance plans, nervous breakdowns when transacting, fear of upgrading or resetting wallets, and more situations that exceed the simple advice of “just write down 12-24 words”.

Which setup should you choose?

If you plan to self-custody a meaningful amount of bitcoin, security should be your top priority. Your setup should be simple enough to avoid mistakes, redundant enough to recover from failure, and strong enough to deter theft.

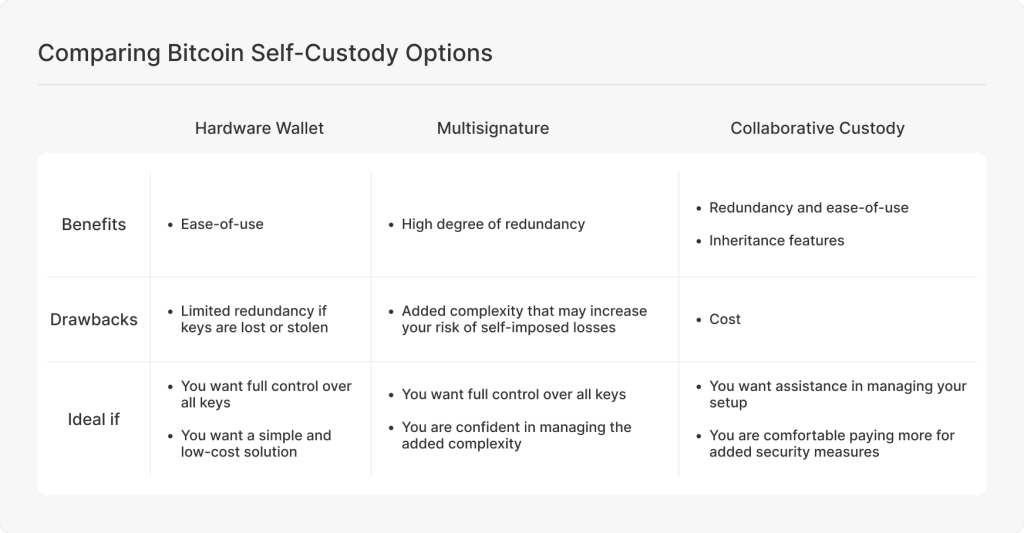

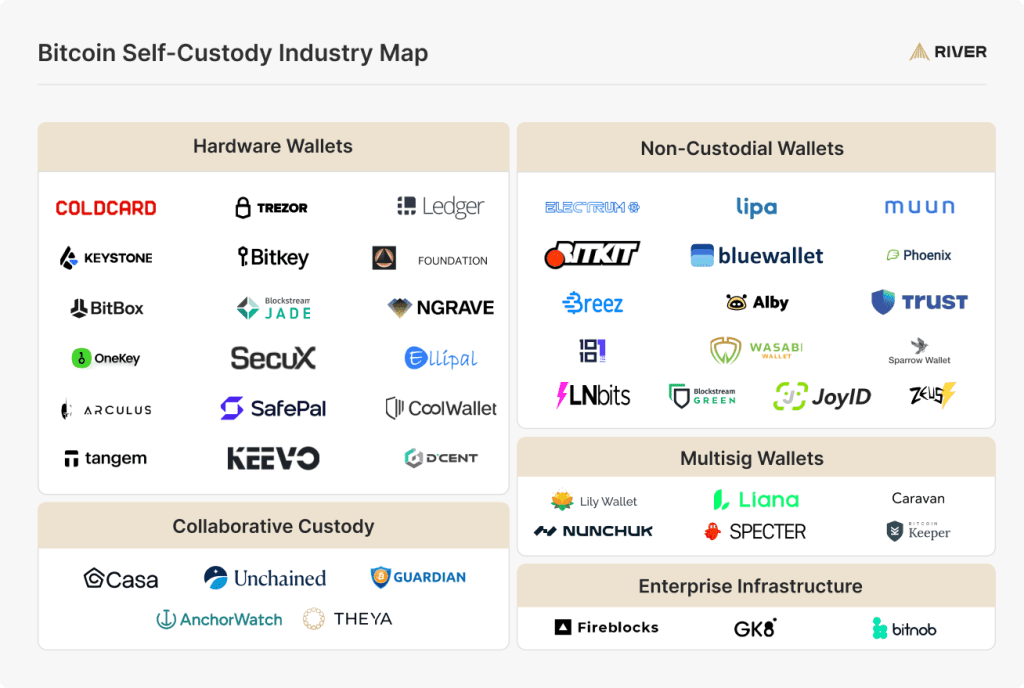

There are three popular categories of self-custody designed for long-term storage:

Hardware wallets are typically used in a simple single-signature setup where you alone control the key needed to spend your funds. As users’ security needs evolve, hardware wallets can also serve as part of more advanced, multi-signature arrangements that require multiple keys to authorize a transaction.

Multisig setups are for individuals who are comfortable with managing multiple independent keys themselves. Multisig can still provide additional protection against certain types of physical theft or device failure. However, it also introduces greater operational complexity, requiring careful coordination across multiple hardware wallets, secure storage of recovery materials for each key, and a clear process for signing transactions without exposing private keys. Properly managing backups and ensuring each device remains accessible and functional over time can be challenging, particularly for non-technical users.

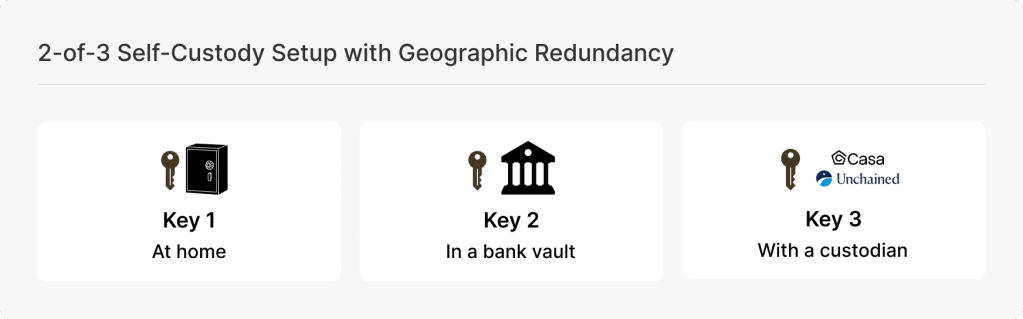

Collaborative custody solutions are well-suited for people without a high degree of technical knowledge who would benefit from professional support. Collaborative models distribute multiple keys between the user and the service provider. A standard setup is a two-of-three multisig arrangement where the user holds two keys, giving them full control over their funds, and the service provider holds a third key as a backup. This eliminates single points of failure; loss of your key or device doesn’t automatically mean loss of funds. Importantly, because users typically have a controlling share of keys, they are not dependent on third parties to transfer coins.

How can you manage your setup securely?

Make sure to consult guides tailored to the specific configuration you choose. Regardless of your setup, be sure to follow these three best practices:

- Redundancy: Eliminate single points of failure. Redundancy dramatically lowers the risk of permanent key loss, transforms rare accidents into recoverable events, and substantially increases the cost of theft. This is because an attacker must compromise multiple independent components such as keys, devices, and storage locations.

- Appropriate hardware use: Hardware devices reduce the risk of online attacks, but only if they’re purchased, operated, and maintained properly.

- Disaster prevention: Full control over your funds means full responsibility for their protection. Plan ahead to reduce the likelihood and impact of any catastrophic event.

Below, we expand on these best practices with practical, setup-specific guidelines. These recommendations are inspired by Casa’s publicly shared approach to collaborative custody and key management.

Store your keys and backups in multiple locations: Keys and backups should be secured in locations that are meaningfully different from one another, so a fire, flood, or burglary cannot compromise everything at the same time. A backup refers to a copy of your seed phrase or recovery key that allows you to restore your wallet if your primary device is lost or destroyed. Backups can take different forms: written seed phrases stored on paper, encrypted digital backups, or steel backups, which are engraved or stamped onto steel plates designed to survive fires, water damage, and physical impact.

A common approach for a 2-of-3 collaborative custody setup is to keep one key at home or on a personal device, one key in a bank vault in a different city, and a third key with the collaborative custody provider. For a single-signature hardware wallet, make sure your seed phrase or recovery key backup is stored in a secure location separate from the hardware device itself, ideally using a durable backup method like steel if long-term reliability is important.

For multisig, use tools from different manufacturers: If you use a collaborative or multisig setup, make sure to use hardware and software wallets from different providers. This reduces your risk to supply chain attacks and bugs.

Buy devices directly from manufacturers, no middlemen: Purchase hardware devices directly from the manufacturer or from trusted, verified resellers, and always set them up yourself. Never use pre-initialized seeds, pre-printed recovery phrases, or “ready-to-use” wallets from third parties; these could have been tampered with, allowing someone else to access your funds later.

Make your transactions with a hardware device: Using your private keys to make bitcoin transactions should remain as secure as possible without introducing undue complexity. For bitcoin you hold in self-custody, hardware devices are the best way to keep your activity offline and safe from attacks, as they do not carry the complexity and risks associated with using a paper wallet.

Do routine maintenance checks of your hardware: To ensure your self-custody setup will work when you need it, it’s important to perform routine maintenance checks. When you first set up a hardware wallet, send a small test transaction and restore the wallet from your seed phrase to confirm that your backup works. The exact steps will vary depending on your setup, so consult the device manufacturer’s documentation to make sure you follow the correct process. You can build confidence by practicing these steps on a hot wallet and referring to our guide on getting started.

Once you’re comfortable with your long-term setup, continue performing test transactions at least once a year. These quick checks help confirm that your device is working properly, your backups are accurate, and you’ll be able to access your funds in an emergency.

Maintain strong privacy: Keeping your information private is the single most effective way to reduce the risk of theft in a self-custody setup because information itself is often the most valuable asset an attacker can obtain. When you reveal how much bitcoin you own, what tools or wallet configurations you use, or even small operational details about your setup, you unintentionally provide clues that can be pieced together into a target profile. Attackers exploit this information to launch social engineering schemes, phishing attempts, or even physical attacks and threats.

Have an inheritance plan: Collaborative custody providers and self-custody advisors typically support inheritance planning that protects your privacy. If you plan to manage your setup on your own, it’s wise to create a plain-language recovery guide in the case of death. The guide should explain what accounts and tools exist, where important materials are stored, who is allowed to help, and how everything can be put together even by someone with no technical background.

Train your executors or heirs ahead of time by running a supervised test recovery using a small, low-value amount. This helps remove confusion and stress long before it matters. Keep the recovery instructions separate from the actual keys so that having the documents alone doesn’t give someone control, but ensure only the right people know how to bring both pieces together when needed.

Make sure you can recover your setup independently: Design your setup so that if you happen to lose a key, it can be recovered using open-source software. That way, you won’t be reliant on a trusted third-party to access your assets. A Coldcard, for example, is fully open source, so anyone can independently verify how recovery works and build compatible tools if the company ever disappeared. Wallets that aren’t open source may require you to trust the vendor’s continued support, because you can’t see how recovery actually works or rebuild their tools yourself.

If you choose to use collaborative custody or a recovery provider, retain a quorum that works even if that provider disappears or refuses service. Validate this independence with occasional signed test transactions so you know each recovery path is viable in practice.

Self-custody solutions

An entire industry now exists to support secure, self-custodial bitcoin storage and transactions. In addition to solutions designed for individual, long-term storage, several other forms of self-custody exist:

Non-custodial wallets, often called software wallets, are mobile or desktop apps that are convenient for payments. Software wallets are best used for smaller balances or as a spending wallet paired with a more secure setup for long-term storage.

Enterprise infrastructure solutions allow larger entities to self-custody with governance and operational controls for their key management.

The Future of Bitcoin Custody

Just as bitcoin is a rapidly maturing asset that has not yet reached its full potential, bitcoin custody is still evolving. Below we highlight trends in bitcoin storage that we expect to continue over time.

Indirect exposure replacing exchange balances

The introduction of spot bitcoin ETFs in January 2024 changed how most bitcoin is bought, sold, and stored.

Historically, exchanges were the primary gateway for bitcoin investment, largely driven by individual investors. The arrival of ETFs brought bitcoin to a broader audience of retail and institutional investors by making it easily accessible through traditional brokerage accounts.

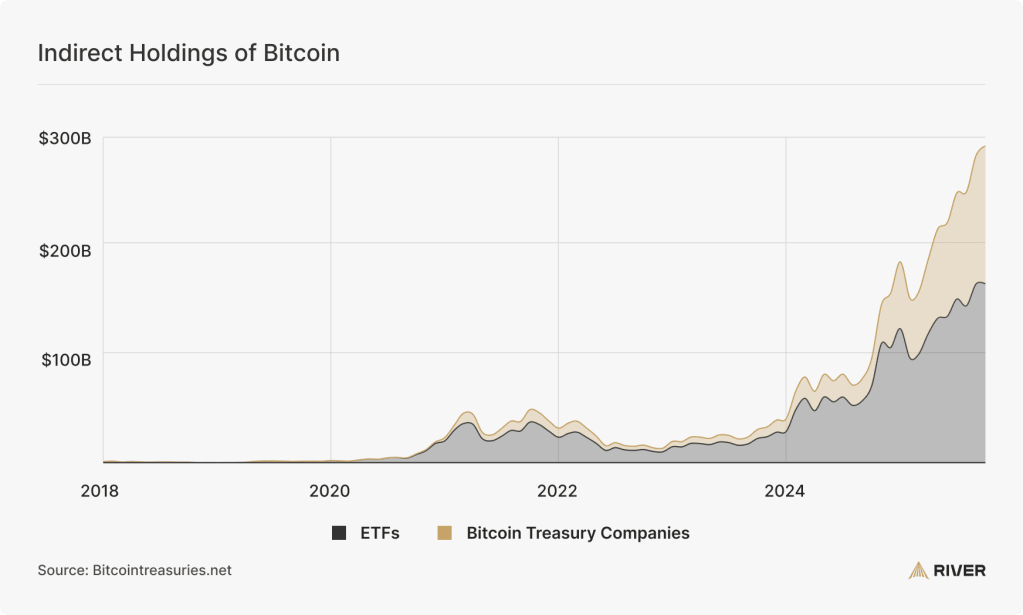

Bitcoin ETFs are the most popular form of indirect exposure to bitcoin, where an investor gains exposure to bitcoin’s price through their brokerage without truly owning the asset. Bitcoin treasury companies are a similar form of indirect exposure; investors gain bitcoin price exposure through ownership of public company shares, rather than bitcoin itself. Together, ETFs and bitcoin treasury companies hold nearly $300 billion in bitcoin, or 11.6% of the total bitcoin supply.

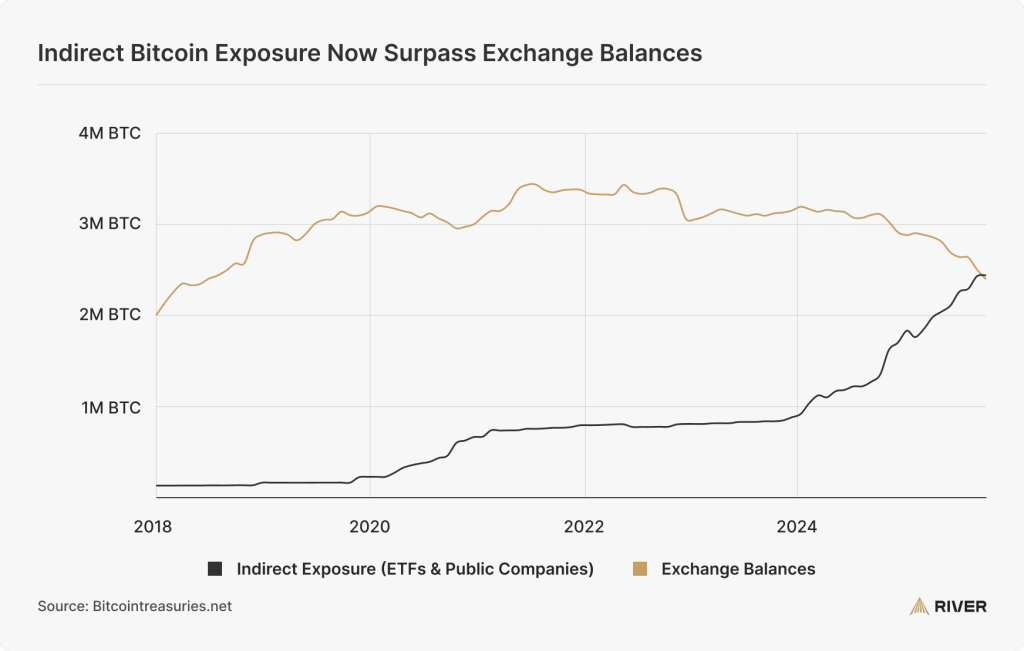

These forms of indirect exposure now represent a larger source of demand for bitcoin than exchanges, and are owned by as many as 50 million Americans and a majority of the largest U.S. hedge funds and registered investment advisors. As a result, more bitcoin is now held through these products than on exchanges.

Institutional investors are still largely underrepresented in bitcoin adoption. For example, U.S. investment advisors are responsible for managing more than $128 trillion in assets, yet currently have a net bitcoin allocation of just 0.006%. Because these investors typically prefer ETFs over direct ownership, indirect exposure is likely to keep growing as adoption among professional investors continues, gradually replacing exchange balances over time.

Transparency becoming a standard for exchanges

Despite the rise of indirect exposure products, exchanges will likely remain the primary way for investors to gain direct ownership of bitcoin. Exchanges know that they will have to work hard to win consumer trust, and thus some have become more transparent in recent years.

The importance of transparency became clear in 2022, when investors lost an estimated 158,000 BTC, worth more than $2.6 billion, due to internal theft and insolvencies caused by exchanges that were lending out customer deposits. In the aftermath of these failures, more than 10 exchanges introduced proof of reserves attestations, designed to demonstrate that client assets are fully backed and held in reserve.

Today, nearly half of all bitcoin held on exchanges can be verified as fully reserved. However, adoption of Proof of Reserves is not yet universal, with 7 of the 10 largest U.S. exchanges lacking this feature. As investor demand for transparency continues to grow, and given the minimal downside to implementing such attestations, Proof of Reserves is likely to become a standard feature across the exchange landscape.

That said, Proof of Reserves is only one dimension of transparency. While it allows users to verify that their bitcoin is in full reserve, it cannot alone guarantee the long-term financial health or operational integrity of an exchange.

An equally important component of transparency is the publication of detailed financial statements, ideally through regular, independently audited disclosures. Exchanges that share income statements, balance sheets, and statements of cash flow allow their clients to better assess their financial health and ability to withstand market downturns or operational stress.

Publicly traded companies such as Coinbase and Robinhood are required to disclose their financials quarterly. In addition, a few privately held exchanges such as Kraken and River have followed suit, publishing financial reports alongside routine proof of reserves audits. Ultimately, this combination of Proof of Reserves and traditional financial transparency represents the highest standard of accountability for exchanges.

Self-custody is becoming more accessible to the masses

Bitcoin adoption is largely limited by accessibility, as demonstrated by the surge of bitcoin ownership following the launch of ETFs in 2024. The same principle applies to self-custody: the simpler and more foolproof self-custody products become, the more people will be capable of using them.

Self-custody has gradually become more user-friendly throughout Bitcoin’s history. The introduction of software wallets in 2011, followed by seed phrases in 2013, dramatically lowered the technical barriers to holding bitcoin on your own.

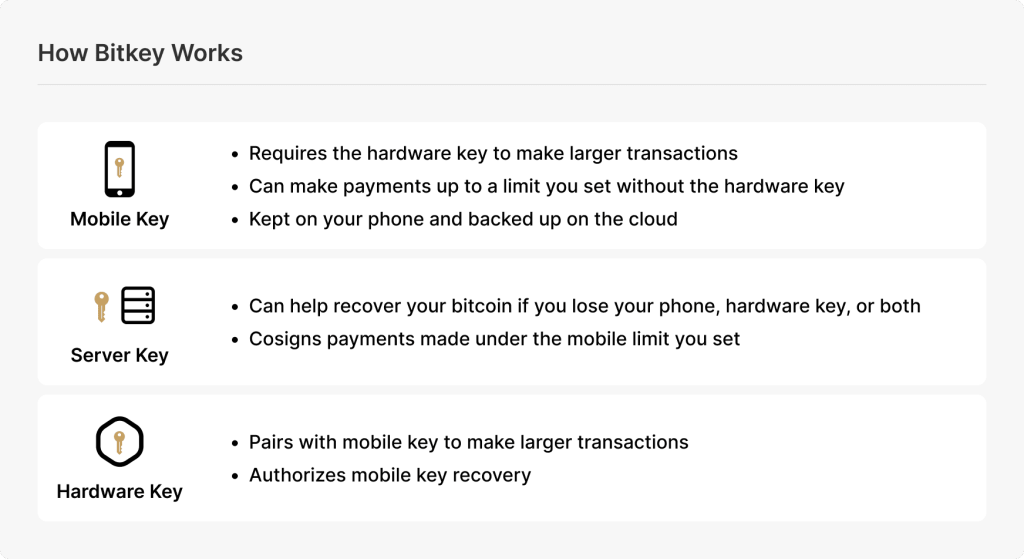

In 2023, Block, the parent company of Cash App and Square, launched Bitkey, a wallet that brought self-custody to the masses through an intuitive design that eliminates seed phrases and single points of failure. Bitkey uses a 2-of-3 multi-signature setup: one key on the user’s phone, one on the Bitkey hardware device, and one held by Block for recovery. Any two keys are required to move Bitcoin, ensuring that no single device or entity can access funds alone. If either the phone or hardware device is lost, the remaining keys can restore access, and if both are lost, the mobile key is securely backed up in the cloud for recovery.

Beyond Bitkey, other self-custody providers are pursuing similar innovations to make bitcoin ownership more secure and accessible. Ledger, for example, now offers NFC recovery keys that replace the traditional 12 or 24-word seed phrase. The company has also introduced a subscription-based Ledger Recover service, which shards a user’s private key among three independent custodians for secure backup. None of these custodians can access funds individually, but the system enables users to recover their wallet in the event of loss, though it introduces privacy tradeoffs due to identity verification requirements.

As more companies develop solutions focused on usability and redundancy, the barriers to secure self-custody will continue to fall, allowing more people to hold their own bitcoin without dependence on intermediaries.

New bitcoin custody models continue to emerge

As this report has shown, bitcoin custody remains an evolving landscape. Below we highlight three innovations, still largely experimental today, that could impact bitcoin custody in the future:

Miniscript and Taproot are redefining programmable custody: Spending policies are simply the rules that decide how bitcoin can be moved: who must approve a withdrawal, how long someone must wait, or what happens if a device is lost.

Miniscript, introduced in 2019, standardized the way bitcoin spending policies are written and analyzed. It allows wallets and custodians to safely implement advanced policies like time locks, fallback keys, and multi-signature rules. For example, a family’s shared wallet could require two approvals for large withdrawals, automatically fall back to a recovery key if someone loses their device, and enforce a 24-hour delay before funds move.

Combined with Taproot (activated in 2021), these policies become more private and efficient: only the rule actually used gets revealed on-chain, while other conditions remain hidden.

Vaults could soon bring protocol-level protection: The concept of “bitcoin vaults” has existed for years, but practical implementation may become viable through a future software upgrade. A vault is like a safety lock on your bitcoin. If someone tries to move your money, the vault adds a built-in delay or extra steps so you have time to notice and stop it. By embedding these controls directly into wallet logic (or potentially into the Bitcoin protocol itself), vaults could significantly reduce theft risk while maintaining user sovereignty and minimizing operational complexity.

Multi-institutional custody is maturing, but not yet mainstream: In a multi-institutional custody (MIC) model, control over bitcoin is distributed among three or more independent custodians, each holding a key. Unlike collaborative custody, MIC remains fully custodial, but the design eliminates single-entity risk. Because no one custodian can move funds unilaterally, the model mitigates counterparty, operational, and even jurisdictional risk. Assets must be held in full reserve, making on-chain proof of reserves an inherent feature of the system. This transparency, combined with regulatory separation between custodians, offers stronger assurances of solvency and integrity than traditional single-entity custody. While adoption is still limited, MIC could potentially prompt a rethinking of how exchanges and institutions store bitcoin.

Conclusion

Bitcoin’s future as incorruptible, global money depends on how safely it can be stored. As an industry, we still have substantial work to do.

For exchanges, universal Proof-of-Reserves, full-reserve practices, rigorous operational controls, and routinely audited financials should be baseline standards, not differentiators. At the same time, self-custody should always be encouraged because it preserves direct ownership and personal sovereignty. It must be simple, resilient, and widely accessible, not limited to experts.

If we raise the floor on security and make self-custody easy by default, bitcoin will scale into a durable, widely held reserve asset, owned directly by the people it serves.

About River

Founded in 2019, River is a financial services company based in Columbus, Ohio. We are proud to help American individuals and businesses take ownership of their finances through Bitcoin, the world’s only incorruptible digital money.

Glossary

Bitcoin Improvement Proposal (BIP): A community standard describing proposed changes or conventions for Bitcoin software or usage.

Counterparty risk: The risk that a third party holding your assets (e.g., an exchange or custodian) fails, misuses funds, or becomes insolvent.

Derivation path: A derivation path is a piece of data which tells a Hierarchical Deterministic (HD) wallet how to derive a specific key within a tree of keys. Derivation paths are used as a Bitcoin standard and were introduced with HD wallets as a part of BIP 32.

Extended public key (Xpub): An extended public key, or xpub, is a public key which can be used to derive child public keys as part of a Hierarchical Deterministic (HD) wallet. An extended public key is a Bitcoin standard established by BIP 32 and is mainly used by a wallet behind the scenes in order to derive public keys.

Hierarchical Deterministic (HD) wallet: A Hierarchical Deterministic (HD) wallet is the term used to describe a wallet which uses a seed to derive public and private keys. HD wallets were implemented as a Bitcoin standard with BIP 32.

Multi-Party Computation (MPC): A signing method where multiple devices/parties jointly produce a valid signature without any single party holding the full private key.

Paper wallet: An offline printout of a private key and address; historically used for cold storage but now considered risky and hard to manage safely.

Private key: A private key is used to send bitcoin which was received by the corresponding public key. When bitcoin is sent to a public key, only a signature produced by the private key can spend that bitcoin.

Rehypothecation: Re-using customer assets (e.g., lending deposits) for the custodian’s purposes, adding counterparty risk.

Seed / mnemonic phrase: A list of 12-24 words used to back up a wallet. This phrase is a representation of a seed, which is the data that generates all of the keys in an HD wallet. A mnemonic phrase is also sometimes referred to as a seed phrase or recovery phrase.

Watch-only wallet: A wallet that can monitor balances and transactions using public information (e.g., xpub) but cannot spend.

Risks of Loss

Clipboard hijacking: A type of malware attack where malicious software monitors a user’s clipboard and replaces copied bitcoin addresses with the attacker’s own address during paste. Because bitcoin transactions are irreversible, victims who fail to notice the altered address lose their funds permanently.

Compromised cloud storage: Occurs when sensitive wallet data, such as seed phrases, private keys, or backups, are stored in cloud services (e.g., Google Drive, iCloud) that become breached or accessible by unauthorized parties. Attackers can use this information to take full control of the associated funds.

Death without succession plan: Refers to the loss of access to bitcoin after the holder passes away without properly sharing recovery information or instructions with heirs. Without clear documentation and access to private keys, bitcoin becomes permanently inaccessible, as there are no legal intermediaries to recover it.

Embezzlement: The internal theft of customer or company assets by employees or executives at custodial institutions or exchanges. It can involve direct misappropriation of funds or manipulation of internal accounting to conceal theft.

Fake wallets: Fraudulent or malicious wallet applications and hardware devices that imitate legitimate products to deceive users into entering seed phrases or transferring funds. These scams often target new users through app stores, phishing links, or counterfeit hardware devices.

Failed backups: Backups that are missing, corrupted, improperly stored, or untested. Without reliable backups of seed phrases or key materials, users risk permanent loss of access in the event of hardware failure, theft, or natural disasters.

Hacks: External attacks exploiting software vulnerabilities, weak security infrastructure, or human error to gain unauthorized access to exchanges, custodians, or personal wallets. Hacks can result in large-scale theft of funds or personal information.

Insider theft: A self-custody loss caused when someone close, such as a relative or friend, gains access to your keys or recovery materials to steal funds. It often results from oversharing custody details or poor privacy around holdings.

Insolvency: When a custodian, exchange, or institution cannot meet its financial obligations, causing customer assets to be frozen or lost.

Malware: Malicious software designed to infiltrate devices, often to steal private keys, seed phrases, or credentials. Malware can disguise itself as wallet software or browser extensions and may also enable clipboard hijacking or remote control of devices.

Phishing attacks: Deceptive emails, websites, or messages that impersonate trusted entities (such as exchanges or wallet providers) to trick users into revealing credentials, private keys, or seed phrases. Phishing is one of the most common entry points for theft.

Phone theft: Physical theft of a mobile device containing wallet apps, two-factor authentication (2FA) codes, or seed phrase backups. If the phone is unsecured or tied to SMS-based authentication, an attacker may gain access to both funds and recovery methods.

Physical threats: Coercive attempts such as extortion, kidnapping, or robbery to force individuals to transfer or disclose access to bitcoin. This risk increases when holdings are publicly known or associated with personal identity.

Regulatory seizures: The confiscation or freezing of assets held by custodial entities under legal or regulatory action.

Scams: Fraudulent schemes that deceive users into voluntarily sending bitcoin or sharing access credentials. Common scams include fake investment opportunities, impersonation of support staff, and Ponzi-style returns promising unrealistic gains.

SIM swap: An attack where criminals convince a mobile carrier to transfer a victim’s phone number to a new SIM card, allowing them to intercept two-factor authentication (2FA) codes and reset login credentials. This can lead to full account takeover.

Software or device failure: Loss of access to wallets due to corrupted software, malfunctioning hardware, or obsolete firmware. Without redundant backups, such failures can result in permanent loss of funds.

Supply-chain attacks: Attacks where an adversary compromises a product before it reaches the end user, such as tampered hardware wallets, pre-initialized seed phrases, or malicious software updates. These attacks exploit trust in the supply chain to access keys or redirect transactions.

Credits

Report created by: Sam Baker, Vincent Lee

Review by: Sam Wouters, Alexander Leishman, Julia Duzon, James Page, Philip Serrano, Grantham Tiefenthaler

Cover design by: Jason Benjamin

Disclaimer

This report was prepared for informational purposes only and does not represent investment advice of any kind. River Financial Inc. does not provide tax, legal, investment, or accounting advice, and this report should not be relied on or construed as such. We recommend performing your own analysis and seeking professional advice before making any financial decisions.

Information contained in the report is based on either our own data or external sources we consider to be reliable. We cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of all data.

River Financial Inc. shall have no liability whatsoever for any actions taken or decisions made as a consequence of the information in this report, including any expenses, losses, or damages, whether direct or indirect. The contents of this report are the property of River Financial Inc. and may not be duplicated or distributed without the prior written consent of River Financial Inc.

You must be logged in to post a comment.